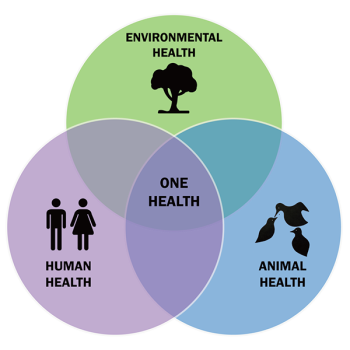

One Health

One Health is a provision that has been included into the various drafts of the WHO Pandemic Treaty, which is still being negotiated.

One Health is a provision that has been included into the various drafts of the Pandemic Treaty, which is still being negotiated.

One Health is an attempt at human control over the whole biosphere: human health, animal health and environmental health.

The One Health approach is hailed by some as a groundbreaking framework for addressing global health challenges but it raises significant concerns regarding national sovereignty, civilian rights, and bureaucratic overreach.

While the concept of integrating human, animal, and environmental health efforts might seem beneficial in theory, its practical implementation reveals potential pitfalls that could undermine the autonomy of nations and individuals alike.

The One Health approach, though hailed as a groundbreaking framework for addressing global health challenges, raises significant concerns regarding national sovereignty, civilian rights, and bureaucratic overreach. While the concept of integrating human, animal, and environmental health efforts might seem beneficial in theory, its practical implementation reveals potential pitfalls that could undermine the autonomy of nations and individuals alike.

1. Erosion of National Sovereignty

One of the most significant criticisms of the One Health approach is its potential to erode national sovereignty. By advocating for global, coordinated actions that transcend national boundaries. One Health could impose external control over domestic policies and practices. This globalised approach requires nations to conform to international standards and regulations, which may not align with their specific needs, cultural values, or political priorities.

Impact on Policy-Making:

Countries may be pressured to adopt policies that favour global health agendas over national interests. For instance, implementing international protocols on disease surveillance or environmental management could limit a nation’s ability to tailor interventions that suit its unique context. This could lead to a loss of control over critical health and environmental decisions, effectively placing the interests of global organisations above those of the world.

2. Bureaucratic Overreach and Centralisation of Power

The One Health approach also risks contributing to an increase in government overreach. The integration of various sectors—such as public health, agriculture, and environmental science—into a unified framework, necessitates the creation of expansive administrative bodies. These organisations can become overly powerful, leading to a concentration of decision-making authority in the hands of a few global institutions or bureaucratic elites.

Lack of Accountability: As power becomes more centralised, there is a danger that these bureaucracies operate with limited transparency and accountability to the public. The complexity of coordinating across multiple sectors and nations can also result in inefficient or ineffective interventions, driven more by political agendas than by evidence-based practices.

Top-Down Approaches: The implementation of One Health initiatives may often follow a top-down model, where decisions are made by international or national bodies without sufficient input from local communities. This can lead to policies that are disconnected from the realities on the ground, exacerbating existing challenges rather than solving them.

3. Threat to Civil Liberties and Individual Rights

The overarching nature of the One Health approach also poses threats to individual rights and civil liberties. By framing health as a global security issue, there is a risk that personal freedoms may be curtailed in the name of public health.

Infringement on Privacy: Integrated surveillance systems (including Digital ID), which are central to One Health, often require the collection and sharing of vast amounts of citizen’s private medical data across sectors and borders. This could lead to invasive monitoring practices that compromise the privacy of individuals and communities.

Coercive Measures: The push for coordinated health responses may also justify coercive measures, such as mandatory vaccinations, isolation or quarantine orders, or restrictions on movement. These actions, while intended to protect public health, can infringe on personal autonomy and our right to make informed choices about our own health and well-being.

4. Overemphasis on Technocratic Solutions

Finally, the One Health approach often prioritises technocratic solutions to complex health problems, relying heavily on scientific and technological interventions. While these solutions can be effective, they also overlook the socio-political and economic factors that contribute to health issues.

Oversimplifying Complex Issues: By focusing predominantly on technical fixes, One Health may reduce complex health challenges to mere problems of disease management, ignoring the broader context in which these issues arise. This reductionist view can lead to interventions that are not only insufficient but also harmful in the long run.

Marginalising of Alternative Approaches: The emphasis on technocratic solutions can marginalise alternative health approaches, including traditional medicine and community-based practices. This can limit the range of available options for addressing any health challenges, particularly in regions where these alternatives are deeply rooted in the culture and history of the people.

Bird flu, or avian influenza, is a viral infection that primarily affects birds and occasionally jumps to humans. The most recent strains of the virus, while causing concern due to their potential for mutation, have not yet resulted in human fatalities. Human cases typically arise from direct contact with infected poultry, and while the disease can cause respiratory symptoms (sometimes severe), the actual risk to humans from the current strain is relatively low.

Mpox, formerly known as MonkeyPox, is a zoonotic disease caused by the monkeypox virus, which can affect both animals and humans. Although Mpox can cause symptoms similar to smallpox, such as fever and rash, it is generally much less severe. Outbreaks have primarily occurred in Central and West Africa, with recent cases outside these regions being relatively mild and treatable. The disease is not highly transmissible between humans, and while it can cause discomfort and complications, the overall threat level is considered moderate.

A One Health “Case Study.”

The application of the One Health approach to managing Mpox in Australia highlights the risks of imposing global

health solutions that may not align with the country’s specific needs or realities. While Australia has the resources

to manage Mpox effectively, the One Health framework can push for measures that may be unnecessary or overly

cautious in the Australian context.

Autonomy in Australia:

- External Influence on Health Policy: The One Health framework can lead to external pressures for

Australia to implement health policies that may not be fully relevant to the local population or may be seen

as overreactions. For example, quarantine measures or vaccination campaigns driven by global concerns

might not be necessary given Australia’s robust healthcare system and lower incidence rates of mpox. - Marginalisation of Local Expertise: The emphasis on global coordination can sometimes overshadow the

expertise of Australian health pratictioners and authorities, who are better equipped to understand and

respond to the specific needs of the Australian population. This can lead to a disconnect between global

recommendations and local realities, reducing the effectiveness of interventions.

Economic and Social Impact:

- Disruption to Local Economies: Measures like movement restrictions, driven by th global One Health

agenda, can disrupt local economies in Australia, particularly in remote or rural areas where economic

activities are closely tied to community well-being. These actions can lead to unintended social and

economic consequences, particularly in areas that are already vulnerable. - Potential for Coercive Health Measures: The focus on preventing Mpox under One Health could lead to

the introduction of coercive health measures in Australia, such as mandatory vaccinations or strict

quarantine protocols. While implemented to “protect public health”, these actions infringe on individual

rights and freedoms, often without significant justification or back-up data.

While the One Health framework seeks to address the complexities of zoonotic diseases through global

coordination, its application in Australia reveals significant risks. The potential for bureaucratic overreach,

economic disruption, and challenges to national sovereignty highlights the need for a more balanced approach that

respects Australia’s autonomy and leverages its local expertise. As Australia continues to manage public health

challenges like bird flu and Mpox, it is crucial to critically assess the role of One Health and ensure that global

health strategies do not come at the expense of local needs and values.